(index page)

We Are Talking Loudly and No One Is Listening

“Listening is not merely not talking, though even that is beyond most of our powers; it means taking a vigorous, human interest in what is being told to us” — Alice Duer Miller

A couple of months ago I wrote about how we need to be advocating for data sharing and data management with more focus on adoption and eliminate discussions about technical backends. I thought this was the key to advocating for getting researchers to change their practices and make data available as part of their normal routines. But, there’s more than just not arguing over platforms that we need to change — we need to listen.

We are talking loudly and saying nothing.

I routinely visit campuses to lead workshops on data publishing (as train the trainers style for librarians and for researchers). Regardless of the material presented, there are always two different conversations happening in the room. At each session, librarians pose technical questions about backend technologies and integrations with scholarly publishing tools (i.e. ORCiD). These are great questions for a scholarly publishing conference but confusing for researchers. This is how workshops start:

Daniella “Who knows what Open Access is?”

<50% researchers in room raised hands

Daniella “Has anyone here been asked to share their data or understand what this means?”

<20% researchers in room raised hands

Daniella “Does anyone here know what an ORCiD is or have one?”

1 person total raised their hand

We are talking too loudly and no one is listening.

We have characterized ‘Open Data’ as successful because we have incentives, and authors write data statements, but this misconception has allowed the library community to focus on scholarly communications infrastructure instead of continuing to work on the issue at hand: sharing research data is not well understood, incentivized, or accessible. We need to focus our efforts on listening to the research community about what their processes are and how data sharing could be a part of these, and then we need to take this as guidance in advocating for our library resources to be a part of lab norms.

We need to be focusing our efforts on education around HOW to organize, manage, and publish data.

Change will come when organizing data to be shared throughout the research process is a norm. Our goal should be to grow adoption of sharing and managing data and as a result see an increase in researchers knowing how to organize and publish data. Less talk about why data should be available, and more hands-on getting research data into repositories, in accessible and researcher-desirable ways.

We need to only build tools that researchers WANT.

The library community has lots of ideas about what is a priority right now in the data world such as curation, data collections, and badges, but we are getting ahead of ourselves. While these initiatives may be shinier and more exciting, it feels like we are polishing marathon trophies before runners can finish a 1 mile jog. And we’re not doing a good job understanding their perspectives on running in the first place.

Before we can convince researchers that they should care about library curation and ‘FAIR’ data, we need to get researchers to even think about managing data and data publishing as a normal activity in research activities. This begins with organization at the lab level and figuring out ways to integrate data publishing systems into lab practice without disrupting normal activity. When researchers are concerned about finishing their experiments, publishing, and their career, it is not an effective or helpful solution to just name platforms they should be using. It is effective to find ways to relieve publishing pain points, and make the process easier. Tools and services for researchers should be understood as ways to make their research and publishing processes easier.

“When you listen, it’s amazing what you can learn. When you act on what you’ve learned, it’s amazing what you can change.” — Audrey McLaughlin

Librarians: this is a space where you can make an impact. Be the translators. Listen to what the researchers want, understand the research day-to-day, and translate to the infrastructure and policy makers what would be effective tools and incentives. If we focus less time and resources on building tools, services, and guides that will never be utilized or appreciated, we can be effective in our jobs by re-focusing on the needs of the research community as requested by the research community. Let’s act like scientists and build evidence-based conclusions and tools. The first step is to engage with the research community in a way that allows us to gather the evidence. And if we do that, maybe we could start translating to an audience that wants to learn the scholarly communication tools and language and we could each achieve our goals of making research available, usable, and stable.

Dash Updates: Fall, 2017

Throughout the summer the Dash team has focused on features that better integrate with researcher workflows. The goal: make data publishing as easy as possible.

With that, here are the releases now up on the Dash site. Please feel free to use our demo site dashdemo.ucop.edu to test features and practice submitting data.

- Dash enabled co-author ORCiDs– all listed co-authors now have the ability to link their ORCiD iD with their data publication.

- Dash notifies “administrators” (set for each instance- campus data librarians & publishing staff) when data are deposited so researchers can get assistance enhancing their metadata (to make data more reproducible, transparent, and discoverable).

- Dash has rich text editing. The abstract, methods, and usage notes fields now have HTML text editors that allow for stylistic text editing to properly format information about the data publication.

- Dash allows for individual file download. All versions of the datasets may now be downloaded at the file-level and not just the entire dataset.

- Dash welcomes UC Davis. Researchers at UC Davis may now publish and share their research data at dash.ucdavis.edu.

- Dash welcomes UC Press journal Elementa. Authors submitting to the Elementa may now utilize UC Press Dash for all data supporting journal publications.

So, what is Dash working on now?

In order to integrate with various aspects of the research workflows, Dash needs an open Rest API. The first API being built is a new deposit API. The team is talking with the repository community and gathering use cases for mapping out how Dash can integrate with journals & online lab notebooks for alternate ways of submitting data that are more in line with researcher workflows.

OA Week 2017: Maximizing the value of research

By John Borghi and Daniella Lowenberg

Happy Friday! This week we’ve defined open data, discussed some notable anecdotes, outlined publisher and funder requirements, and described how open data helps ensure reproducibility. To cap off open access week, let’s talk about one of the principal benefits of open data- it helps to maximize the value of research.

Research is expensive. There are different ways to break it down but, in the United States alone, billions of dollars are spent funding research and development every year. Much of this funding is distributed by federal agencies like the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the National Science Foundation (NSF), meaning that taxpayer dollars are directly invested in the research process. The budgets of these agencies are under pressure from a variety of sources, meaning that there is increasing pressure on researchers to do more with less. Even if budgets weren’t stagnating, researchers would be obligated to ensure that taxpayer dollars aren’t wasted.

The economic return on investment for federally funded basic research may not be evident for decades and overemphasizing certain outcomes can lead to the issues discussed in yesterday’s post. But making data open doesn’t just refer to giving access other researchers, it also means giving taxpayers access to the research they paid for. Open data also enables reuse and recombination, meaning that a single financial investment can actually fund any number of projects and discoveries.

Research is time consuming. In addition to funding dollars, the cost of research can be measured in the hours it takes to collect, organize, analyse, document, and share data. “The time it takes” is one of the primary reasons cited when researchers are asked why they do not make their data open. However, while certainly takes time to ensure open data is organized and documented in such a way as to enable its use by others, making data open can actually save researchers time over the long run. For example, one consequence of the file drawer problem discussed yesterday is that researchers may inadvertently redo work already completed, but not published, by others. Making data open helps prevents this kind of duplication, which saves time and grant funding. However, the beneficiaries of open data aren’t just for other researchers- the organization and documentation involved in making data open can help researchers from having to redo their own work as well.

Research is expensive and time consuming for more than just researchers. One of the key principles for research involving human participants is beneficence– maximizing possible benefits while minimizing possible risks. Providing access to data by responsibly making it open increases the chances that researchers will be able to use it to make discoveries that result in significant benefits. Said another way, open data ensures that the time and effort graciously contributed by human research participants helps advance knowledge in as many ways as possible.

Making data open is not always easy. Organization and documentation take time. De-identifying sensitive data so that it can be made open responsibly can be less than straightforward. Understanding why doesn’t automatically translate into knowing how. But we hope this week we’ve given you some insight into the advantages of open data, both for individual researchers and for everyone that engages, publishes, pays for, and participates in the research process.

OA Week 2017: Transparency and Reproducibility

By John Borghi and Daniella Lowenberg

Yesterday we talked about about why researchers may have to make their data open, today let’s start talking about why they may want to.

Though some communities have been historically hesitant to do so, researchers appear to be increasingly willing to share their data. Open data even seems to be associated with a citation advantage, meaning that as datasets are accessed and reused, the researchers involved in the original work continue to receive credit. But open data is about more than just complying with mandates and increasing citation counts, it’s also about researchers showing their work.

From discussions about publication decisions to declarations that “most published research findings are false”, concerns about the integrity of the research process go back decades. Nowadays, it is not uncommon to see the term “reproducibility” applied to any effort aimed at addressing the misalignment between good research practices, namely those emphasizing transparency and methodological rigor, and academic reward systems, which generally emphasize the push to publish only the most positive and novel results. Addressing reproducibility means addressing a range of issues related to how research is conducted, published, and ultimately evaluated. But, while the path to reproducibility is a long one, open data represents a crucial step forward.

“While the path to reproducibility is a long one, open data represents a crucial step forward.”

One of the most popular targets of reproducibility-related efforts is p-hacking, a term that refers to the practice of applying different methodological and statistical techniques until non-significant results become significant. The practice of p-hacking is not always intentional, but appears to be quite common. Even putting aside some truly astonishing headlines, p-hacking has been cited as a major contributor to the reproducibility crisis in fields such as psychology and medicine.

One application of open data is sharing the datasets, documentation, and other materials needed to reproduce the results described in a journal article, thus allowing other researchers (including peer reviewers) can check for errors and ensure that the conclusions discussed in the paper are supported by the underlying data and methods. This type of validation doesn’t necessarily prevent p-hacking, but it does increase the degree to which researchers are accountable for explaining marginally significant results.

But the impact of open data on reproducibility goes far beyond just combatting p-hacking. Publication biases such as the file drawer problem, which refers to the tendency of researchers to publish papers describing studies that resulted in positive results while regulating studies that resulted in negative or nonconfirmatory results to the proverbial file drawer. Along with problems related to small sample sizes, this tendency majorly skews the effects described in the scientific literature. Open data provides a means for opening the file drawer, allowing researchers to share all of their results- even those that are negative or nonconfirmatory.

“Open data provides a means for opening the file drawer, allowing researchers to share all of their results- even those that are negative or nonconfirmatory.”

Open data is about researchers showing their work, being transparent about their how they make their conclusions, and providing their data for others to use and evaluate. This allows for validation and helps combat common but questionable research practices like p-hacking. But open data also helps advance reproducibility efforts in a way that is less confrontational, but allowing researchers to open the file drawer and share (and get credit for) all of their work.

OA Week 2017: Policies, Resources, & Guidance

By John Borghi and Daniella Lowenberg

Yesterday, through quotes and anecdotes, we outlined reasons why researchers should consider making their data open. We’ll dive deeper into some of these reasons tomorrow and on Friday, but today we’re focused on mandates.

Increasingly funding agencies and scholarly publishers are mandating that researchers open up their data. Different agencies and publishers have different policies so, if you are a researcher, it can be difficult to understand exactly what you need to do and how you should go about doing it. To help, we’ve compiled a list of links and resources.

Funder Policy Guidance:

The links below outline US federal funding policies as well as non profit and private funder policies. We also recommend getting in touch with your Research Development & Grants office if you have any questions about how the policy may apply to your grant funded research.

US Federal Agency Policies:

http://datasharing.sparcopen.org/data

http://www.library.cmu.edu/datapub/sc/publicaccess/policies/usgovfunders

Global & Private Funder Policies:

https://www.gatesfoundation.org/How-We-Work/General-Information/Open-Access-Policy

https://wellcome.ac.uk/funding/managing-grant/policy-data-software-materials-management-and-sharing

Publisher Policy Guidance:

Below are a list of publishers that oversee thousands of the world’s journals and their applicable data policies. If you have questions about how to comply with these policies we recommend getting in touch with the journal you are aiming to submit to during the research process or before submission to expedite peer review and comply with journal requirements. It is also important to note that if the journal you are submitting to requires data to be publicly available this means that the data underlying the results and conclusions of the manuscript must be submitted, not necessarily the entire study. These data are typically the values behind statistics, data extracted from images, qualitative excerpts, and data necessary to replicate the conclusions.

PLOS: http://journals.plos.org/plosone/s/data-availability

Elsevier: https://www.elsevier.com/about/our-business/policies/research-data#Policy

Springer-Nature: https://www.springernature.com/gp/authors/research-data-policy/springer-nature-journals-data-policy-type/12327134

PNAS: http://www.pnas.org/site/authors/editorialpolicies.xhtml#xi

Resources, Services, and Tools (The How)

Thinking about and preparing your data for publication and free access requires planning before and during the research process. Check out the free Data Management Plan (DMP) Tool: www.dmptool.org

For researchers at participating UC campuses, earth science and ecology (DataONE), and researchers submitting to the UC Press journals Elementa and Collabra, check out Dash, a data publishing platform: dash.ucop.edu

We also recommend checking out www.re3data.org and https://fairsharing.org for standards in your field and repositories both in your field or generally that will help you meet funder and publisher requirements and make your data open.

If you are a UC researcher, click on the name of your campus below for library resources to support researchers with managing, archiving, and sharing research data

OA Week 2017: Stories & Testimonials

By John Borghi and Daniella Lowenberg

Because of the tools and services we offer, we here at UC3 spend a lot of time talking about how to make data open. But, for open access week, we’d also like to take some time to talk about why. We think this is best illustrated by comments we collected from the community as well as excerpts from publications and public statements:

Open Data in order to have a broader reach with your work

Dr. Jonathan Eisen (UC Davis): “Starting in about 2009, we started publishing “data papers” to go with our open release of genome sequence data. These papers just report on the generation of the genome data and not analysis of the data. And these data reports have led to a large number of citations for me and my collaborators. For example for the Genomic Encyclopedia of Bacteria and Archaea project, we have published > 100 genome sequence data reports and these have in total been cited at least a few thousand times.

It is a win win approach for us. We publish papers detailing the generation of open data, which in turn I believe makes people feel more comfortable using that data, when they use the data they cite the papers, and we get more academic and general credit for the data. In the past, when people used our data in Genbank when there was no specific paper on just that data set, people were less likely to cite it.”

Open Data in order to find cures

In order to “measure progress by improving patient outcomes, not just publications”, open data is a central feature of the Cancer Moonshot Initiative led by former vice president Joe Biden. Similarly, efforts like clinicaltrials.gov and healthdata.gov aim to expose high value data in the hopes of facilitating better health outcomes.

Open Data in order to aid with the peer review process

Meghan Byrne (Senior Editor, PLOS ONE): “In our experience at PLOS ONE, making data openly available to the reviewers can help move the review process forward more quickly, particularly if the data are clearly reported, with the relevant metadata. In fact, we find that an increasing number of Academic Editors and reviewers are requesting to see the data, so having them ready at the time of submission can help reduce the time to publication. Once the paper is published, making the data publicly available increases the overall impact of the work.”

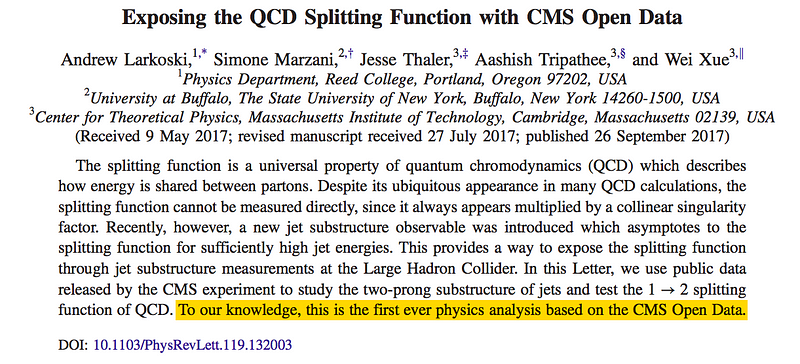

Open Data in order to advance scientific discovery

Open data from the Compact Muon Solenoid (CMS) at CERN’s Large Hadron Collider was recently used by researchers outside the organization to confirm a hypothesis about quantum chromodynamics (read more here). Though this is only one example, it is demonstrative of the immense potential for open data to facilitate discovery as new methods and analyses are applied to old data.

Open Data in order to extend the value of research investment

Carly Strasser (Moore Foundation): “We want research that we fund to be widely available. Free and open access to the research outputs that we fund is critical for ensuring maximum impact.”

Welcome to OA Week 2017!

By John Borghi and Daniella Lowenberg

It’s Open Access week and that means it’s time to spotlight and explore Open Data as an essential component to liberating and advancing research.

Let’s Celebrate!

Who: Everyone. Everyone benefits from open research. Researchers opening up their data provides access to the people who paid for it (including taxpayers!), patients, policy makers, and other researchers who may build upon it and use it to expedite discoveries.

What: Making data open means making it available for others to use and examine as they see fit. Open data is about more than just making the data available on its own, it is also about opening up the tools, materials, and documentation that describes how the data were collected and analyzed and why decisions about the data were made.

When: Data can be made open anytime a paper is published, anytime null or negative results are found, anytime data are curated. All the open data, all the time.

Where: If you are a UC researcher, resources free to you are available at each of your campuses Research Data Management library websites. Dash is a data publication platform to make your data open and archived for participating UC campuses, UC Press, and DataONE’s ONEShare. For more open data resources, check out our upcoming post on Wednesday, October 25th.

Why: Data are what support conclusions, discoveries, cures, and policies. Opening up articles for free access to the world is very important, but the articles are only so valuable without the data that went into them.

Follow this week as we cover policies, user stories, resources, economics, and justifications for why researchers should all be making their (de-identified, IRB approved) data freely available.

Tweet to us @UC3CDL with any questions, comments, or contributions you may have.

Upcoming Posts

Tuesday, October 24th: Open Data in Order to… Stories & Testimonials

Wednesday, October 25th: Policies, Resources, & Guidance on How to Make Your Data Open

Thursday, October 26th: Open Data and Reproducibility

Friday, October 27th: Open Data and Maximizing the Value of Research

EZID: now even easier to manage identifiers

EZID, the easy long-term identifier service, just got a new look. EZID lets you create and maintain ARKs and DataCite Digital Object Identifiers (DOIs), and now it’s even easier to use:

- One stop for EZID and all EZID information, including webinars, FAQs, and more.

Image by Simon Cousins - A clean, bright new look.

- No more hunting across two locations for the materials and information you need.

- NEW Manage IDs functions:

- View all identifiers created by logged-in account;

- View most recent 10 interactions–based on the account–not the session;

- See the scope of your identifier work without any API programming.

- NEW in the UI: Reserve an Identifier

- Create identifiers early in the research cycle;

- Choose whether or not you want to make your identifier public–reserve them if you don’t;

- On the Manage screen, view the identifier’s status (public, reserved, unavailable/just testing).

In the coming months, we will also be introducing these EZID user interface enhancements:

- Enhanced support for DataCite metadata in the UI;

- Reporting support for institution-level clients.

So, stay tuned: EZID just gets better and better!